Faith in Awakening

Bodhisaddha means Faith in Awakening. First we develop the faith in the Buddha’s Awakening. We believe it to be possible and we take his teachings to heart and practice them. When we do, we can see peace and wisdom develop in our hearts, and we start to believe that our own Awakening is possible. The monastery is a place for monks and laypeople to develop this Awakening.

The Thai Forest tradition is one branch of the Theravāda Buddhist tradition. Theravāda Buddhism, also known as the Southern School of Buddhism, is present throughout Thailand, Burma, Sri Lanka, Laos, and Cambodia. The Theravāda tradition is grounded in the discourses recorded in the Pāli Canon, the oldest Buddhist scriptures. Theravāda literally means “the Doctrine of the Elders” and is named so because of its scrupulous adherence to the original teachings and rules of monastic discipline expounded by the Buddha.

The Theravāda Buddhist tradition within Thailand is composed of many different strands and types of monasteries. Most villages and towns in Thailand have at least one monastery, which might serve as a place for ceremony, prayer, cultural activity, education and medicine. Thai monasteries differ widely and express a range of functions and approaches to monastic life. Some monasteries focus on chanting and ceremonies; some on study and intellectual pursuits; some on healing and blessings; some on practice and meditation. In city monasteries, monks are often encouraged to focus on study and administrative duties, with a little meditation on the side. In addition to varying in their approach to monastic life, monasteries also differ widely in terms of how meticulously they uphold the Vinaya, the Buddhist code of monastic discipline.

The Thai Forest tradition is the branch of Theravāda Buddhism in Thailand that most strictly upholds the original monastic rules of discipline laid down by the Buddha. The Forest tradition also most strongly emphasizes meditative practice and the realization of enlightenment as the focus of monastic life. Forest monasteries are primarily oriented around practicing the Buddha’s path of contemplative insight, including living a life of discipline, renunciation, and meditation in order to fully realize the inner truth and peace taught by the Buddha. Living a life of austerity allows forest monastics to simplify and refine the mind. This refinement allows them to clearly and directly explore the fundamental causes of suffering within their heart and to inwardly cultivate the path leading toward freedom from suffering and supreme happiness. Forest monastics live frugally with few possessions. This fosters the joy of an unburdened life and assists Forest monastics in subduing greed, pride, and other taints that abound in the mind.

Forest monastics live in daily interaction with and dependence upon the lay community. While laypeople provide the material supports for the renunciant life, such as alms food and cloth for robes, the monks provide the laity with teachings and spiritual inspiration. Forest monks follow an extensive 227 rules of conduct. They are required to be celibate, to eat only between dawn and noon, and not to handle money. They also engage in a practice known as “tudong” (Thai; derived from the Pāli “dhutaṅga” meaning “austere practice”) in which they wander on foot through the countryside, either on pilgrimage or in search of solitary retreat places in nature. During such wanderings, monks sleep wherever is available and eat only what is offered by lay people along the way.

Origins of Contemporary Thai Buddhism

By the middle of the nineteenth century, Buddhism in Thailand had generally become corrupted with lax monastic discipline, teachings straying from the original texts, little emphasis on meditation, and a widespread belief that spiritual accomplishments were no longer possible. In the midst of this waning tradition, determined Buddhist practitioners returned again to the basics of forest living, moral discipline, and meditation in search of the Buddha’s path to enlightenment. The spiritual determination and accomplishments of these forest practitioners led to the emergence of the contemporary Forest tradition in northeast Thailand. The northeast is one of the most remote and poor areas in Thailand, notable both for its harsh land and its remarkably good-humored people; and now for its wise meditation masters.

The emergence of the contemporary Forest tradition is associated largely with Ajahn Mun and his teacher and contemporary, Ajahn Sao. Both were the sons of peasant farmers in the northeast of Thailand. Ajahn Mun was born in the 1870s in Ubon province near the borders of Laos and Cambodia. He trained under the forest monk Ajahn Sao, vigorously practicing meditation, and then turned to a life of ascetic wandering and meditation practice in the wilderness. Ajahn Mun became a great teacher and exemplar of high standards of conduct. Almost all of the accomplished and revered meditation masters of twentieth century Thailand were either his direct disciples or influenced by him. One of these great meditation masters following in his example was Ajahn Chah.

Historical Significance of Forest Monasticism

The Forest tradition began in the time of the Buddha and has waxed and waned throughout Buddhist history. In one sense, the tradition even predates the Buddha, as it was a common practice of spiritual seekers in ancient India to leave the life of town and village and wander in the wilderness and mountains. The Buddha himself joined this tradition at the age of twenty-nine, giving up his life as a prince in order to seek the way beyond birth, aging, sickness, and death.

The Buddha was born in the forest, enlightened in the forest, taught in the forest, and passed away in the forest. Many of his greatest disciples, such as Venerable Añña-Koṇḍañña and Venerable Mahā Kassapa, were strict forest dwellers who maintained an austere renunciant lifestyle. The Buddha allowed determined forest-dwelling monks, such as these two, to cultivate thirteen special austere practices, called dhutaṅga (a word from the ancient Pāli language). Dhutaṅga literally means “shaking off,” as in shaking off those material and mental qualities which keep a person clinging and attached. These special renunciation practices limit a monk’s or nun’s robes, food, and dwelling places. The practice of dwelling in natural places provided the fundamental backdrop for Forest monasticism throughout Theravada Buddhist history.

The Buddha’s disciples who chose to undertake these dhutaṅga practices and live austerely in the forest did so for many reasons: because dwelling in the wilderness with its rugged and dangerous qualities provided an excellent arena for spiritual training and overcoming fear; because the wilderness with its simplicity, quietude, and natural beauty provided a place for pleasant, peaceful abiding and joyful meditative concentration; because basic forest living allowed the monks to be more easily taken care by the laity as opposed to monks who dwelled in cities; and because living in the forest helped these monks compassionately set an example for future generations.

The practices of these early forest dwellers epitomized the Buddha’s teachings and exemplified his path to liberation. Since the Buddha’s time, the discipline of the monastic order as a whole and the vitality and integrity of the Buddha’s teachings have experienced cycles of growth and decline, of deterioration and revival. Throughout these cycles, the original ethos of the Buddha’s teachings has been preserved and revitalized through the example of these early forest-dwelling disciples and through the efforts of later monastics who followed in their footsteps seeking to live lives focused on meditation practice, simplicity, and renunciation.

The way of practice, the teachings, and the code of monastic conduct which the Buddha expounded 2500 years ago, run deeply against the grain of worldly concerns such as material success, acquisition, wealth, power, fame, pleasure and status. The presence of a monastic order can be a great boon to a society by providing a source of wisdom, peace, and clarity that transcends these worldly concerns. Alternatively, worldly concerns can enter into and distort monastic life. One way this has happened in Buddhist history is that when monks and nuns became accomplished in their practice and became well-known teachers, they drew to their monasteries many visitors bearing gifts and offerings. The success and reputation of these teachers drew wealth, power, and fame to the monastery. Without constant heedfulness, the ways of the world could enter into the monastic order, generating corrupt monastic institutions. In such times, the practice of Forest monasticism by wise and charismatic teachers concerned with spiritual living, discipline, and meditation, rather than institutional rank and official responsibility, played a crucial role in revitalizing the original ethos of the Buddha’s teachings.

(from Abhyagiri.org)

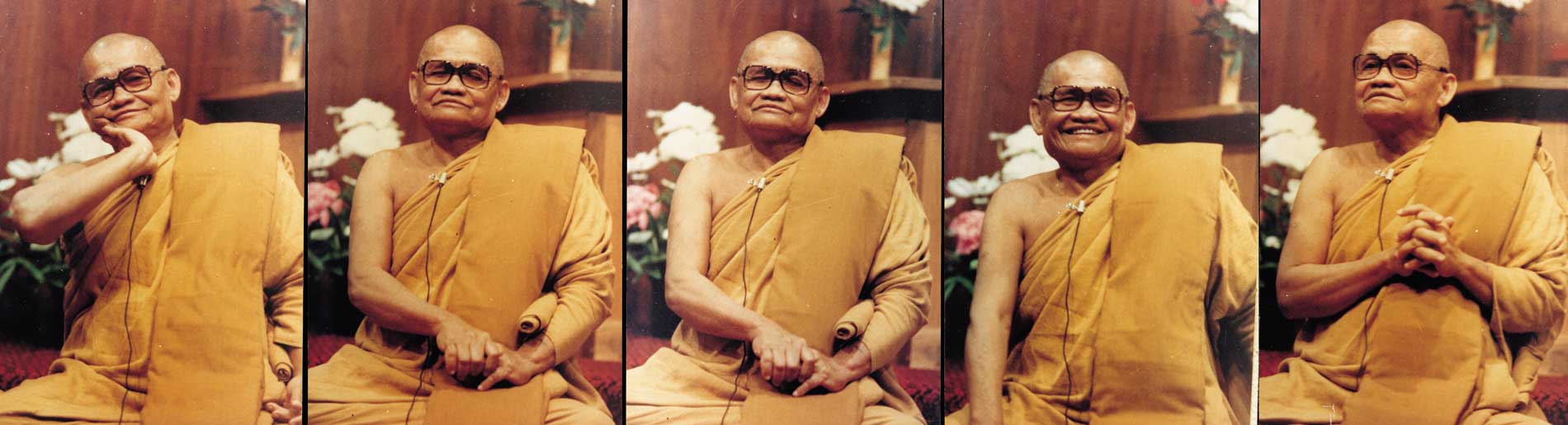

Venerable Ajahn Chah was born on June 17, 1918 in a small village near the town of Ubon Ratchathani, North-East Thailand. After finishing his basic schooling, he spent three years as a novice before returning to lay life to help his parents on the farm. At the age of twenty, however, he decided to resume monastic life, and on April 26, 1939 he received upasampadā (bhikkhu ordination). Ajahn Chah’s early monastic life followed a traditional pattern, of studying Buddhist teachings and the Pali scriptural language. In his fifth year his father fell seriously ill and died, a blunt reminder of the frailty and precariousness of human life. It caused him to think deeply about life’s real purpose, for although he had studied extensively and gained some proficiency in Pali, he seemed no nearer to a personal understanding of the end of suffering. Feelings of disenchantment set in, and finally, in 1946 he abandoned his studies and set off on mendicant pilgrimage.

He walked some 400 km to Central Thailand, sleeping in forests and gathering almsfood in the villages on the way. He took up residence in a monastery where the vinaya, (monastic discipline), was carefully studied and practised. While there he was told about Venerable Ajahn Mun Bhuridatta, a most highly respected meditation master. Keen to meet such an accomplished teacher, Ajahn Chah set off on foot for the Northeast in search of him.

At this time Ajahn Chah was wrestling with a crucial problem. He had studied the teachings on morality, meditation and wisdom, which the texts presented in minute and refined detail, but he could not see how they could actually be put into practice. Ajahn Mun told him that although the teachings are indeed extensive, at their heart they are very simple. With mindfulness established, if it is seen that everything arises in the heart-mind, right there is the true path of practice. This succinct and direct teaching was a revelation for Ajahn Chah, and transformed his approach to practice. The Way was clear.

For the next seven years Ajahn Chah practiced in the style of the austere Forest Tradition, wandering through the countryside in quest of quiet and secluded places for developing meditation. He lived in tiger and cobra infested jungles, using reflections on death to penetrate to the true meaning of life. On one occasion he practised in a cremation ground, to challenge and eventually overcome his fear of death. While he was in the cremation ground, a rainstorm left him cold and drenched, and he faced the utter desolation and loneliness of a wandering homeless monk.

In 1954, after years of wandering, he was invited back to his home village. He settled close by, in a fever ridden, haunted forest called ‘Pah Pong’. Despite the hardships of malaria, poor shelter and sparse food, disciples gathered around him in increasing numbers. This was the beginning of the first monastery in the Ajahn Chah tradition, Wat Pah Pong. With time branch monasteries were established at other locations.

In 1967 an American monk came to stay at Wat Pah Pong. The newly ordained Venerable Sumedho had just spent his first Vassa (‘Rains’ retreat) practicing intensive meditation at a monastery near the Laotian border. Although his efforts had borne some fruit, Venerable Sumedho realized that he needed a teacher who could train him in all aspects of monastic life. By chance, one of Ajahn Chah’s monks, one who happened to speak a little English, visited the monastery where Venerable Sumedho was staying. Upon hearing about Ajahn Chah, he asked to take leave of his preceptor, and went back to Wat Pah Pong with the monk. Ajahn Chah willingly accepted the new disciple, but insisted that he receive no special allowances for being a Westerner. He would have to eat the same simple almsfood and practice in the same way as any other monk at Wat Pah Pong. The training there was quite harsh and forbidding. Ajahn Chah often pushed his monks to their limits, to test their powers of endurance so that they would develop patience and resolution. He sometimes initiated long and seemingly pointless work projects, in order to frustrate their attachment to tranquility. The emphasis was always on surrendering to the way things are, and great stress was placed upon strict observance of the vinaya.

In the course of events, other Westerners came through Wat Pah Pong. By the time Venerable Sumedho was a bhikkhu of five vassas, and Ajahn Chah considered him competent enough to teach, some of these new monks had also decided to stay on and train there. In the hot season of 1975, Venerable Sumedho and a handful of Western bhikkhus spent some time living in a forest not far from Wat Pah Pong. The local villagers there asked them to stay on, and Ajahn Chah consented. The Wat Pah Nanachat (‘International Forest Monastery’) came into being, and Venerable Sumedho became the abbot of the first monastery in Thailand to be run by and for English-speaking monks.

In 1977, Ajahn Chah was invited to visit Britain by the English Sangha Trust, a charity with the aim of establishing a locally-resident Buddhist Sangha. He took Venerable Sumedho and Venerable Khemadhammo along to England. Seeing the serious interest there, he left them in London at the Hampstead Vihara, with two of his other Western disciples who were then visiting Europe. He returned to Britain in 1979, at which time the monks were leaving London to begin Chithurst Buddhist Monastery in Sussex. He then went on to America and Canada to visit and teach. After this trip, and again in 1981, Ajahn Chah spent the ‘Rains’ away from Wat Pah Pong, since his health was failing due to the debilitating effects of diabetes. As his illness worsened, he would use his body as a teaching, a living example of the impermanence of all things. He constantly reminded people to endeavor to find a true refuge within themselves, since he would not be able to teach for very much longer. Before the end of the ‘Rains’ of 1981, he was taken to Bangkok for an operation. However, the procedure did little to improve his condition.

Within a few months he stopped talking, and gradually he lost control of his limbs until he was virtually paralyzed and bedridden. From then on, he was diligently and lovingly nursed and attended by devoted disciples, grateful for the occasion to offer service to the teacher who so patiently and compassionately showed the Way to so many.

Venerable Ajahn Anan Akiñcano was born in the provincial town of Saraburi, Central Thailand, on the 31st of March, 1954, with the name of Anan Chan-in. From an early age he would regularly accompany his parents to the local temple to chant and pay respects to the monks, and he recalls experiencing feelings of great ease and joy whenever looking at images of the Buddha. During his school days he was known to be well-mannered and keen in his studies, and after graduation was hired as an accountant at Siam Cement Company. Though a diligent employee, he found himself increasingly drawn to Buddhist practice and began living at a nearby monastery during his hours away from work.

For the next year, working as an accountant and strictly observing the eight precepts of a lay practitioner, he was able to increase his meditation efforts and his confidence in the Buddha’s teachings. After offering food to the monks each morning, he would travel to work and then return to the monastery in the evening to practice mediation. One day he had an experience of profound insight into the nature of all phenomena, followed by three days and three nights of a happiness unlike anything he had felt before. This experience removed any remaining doubts about committing his life to the Buddha’s teachings, and soon afterwards he decided to enter the monastic order.

On July 3rd, 1975, he took full ordination under his preceptor and teacher, the Venerable Ajahn Chah. He was given the Pali name Akiñcano, meaning “one without worries,” and spent the next four years diligently practising meditation and developing care and attentiveness around the more routine aspects of monastic life. During this period he acted as Ajahn Chah’s personal attendant, which provided him with the opportunity to develop a close connection with his teacher. Though his meditation was up and down during these early years as a monk, in his fourth year it reached a point where it did not decline again.

After the intensive training period with Ajahn Chah, he was allowed the opportunity to seek out more secluded places to further his efforts in meditation. Living in remote forests and charnel grounds, he met with various hardships both outside and within. Still, he committed himself to this way of life for several years, growing in endurance, contending with serious bouts of malaria which took him close to death on many occasions. In 1984 he was offered a section of uninhabited land on which to build a forest monastery. Accompanied by two other monks and a novice, the group settled in the dense forest of Rayong province at what is now known as Wat Marp Jan, “Monastery of the Moonlit Mountain.”

Nearly 25 years later, Ajahn Anan’s reputation as a meditation master has grown, along with the number of monks coming to practice under him and seek his guidance. The monastery and the surrounding area have developed considerably since the time of his arrival, reflecting both Ajahn Anan’s presence and his contribution to the region. Today, he attends to his many duties as abbot and teacher, sharing his time between monks and lay guests and looking after a growing number of branch monasteries.

Bodhisaddha Forest Monastery was opened since April 2012. The original intention of the donors of the land was to develop and maintain a monastery that follows the practice of the Thai Forest Tradition, especially the Venerable Ajahn Chah lineage, which has been responsible for the spreading of the Dhamma to the West.

The opening of the monastery on the 20th April 2012, was officiated by Venerable Ajahn Anan Akiñcano, who led the ordination of 9 novice monks and 25 lay women practitioners for 7 days. It was a very auspicious time that also coincided with the 10th Anniversary of Bodhikusuma Buddhist & Meditation Centre in the city. Many people came for the opening and the people were overjoyed that there would be a new monastery starting up near them.

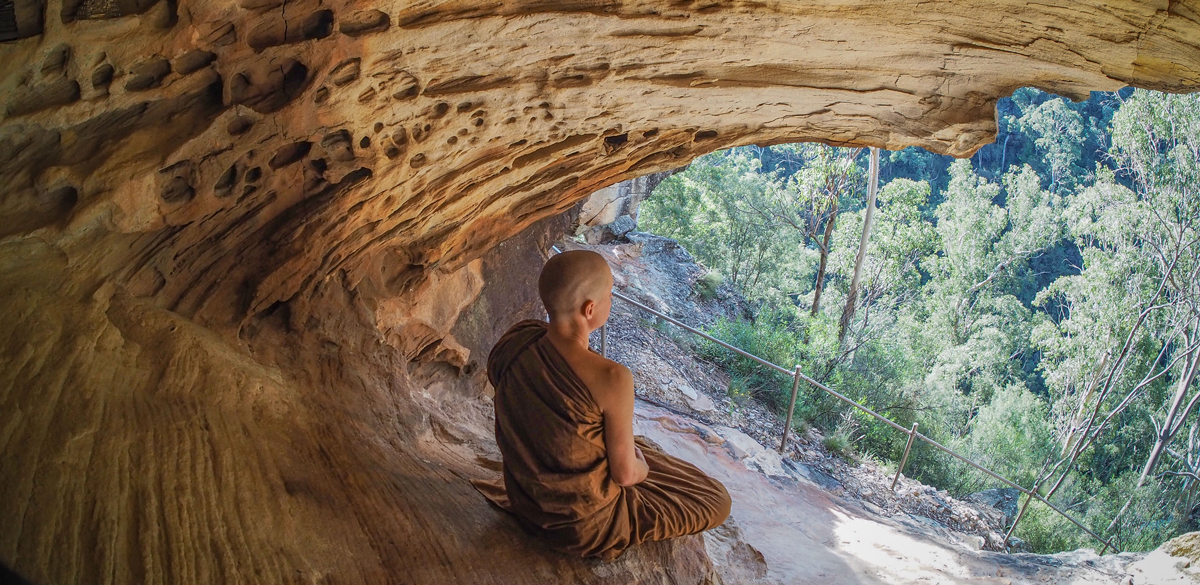

Many monks have come to visit the land already and remarked that it is an appropriate setting for a forest monastery. Comprised of 70 acres of mainly flat land, there is cleared area suitable for future buildings, but enough forest for each future dwelling to have seclusion and privacy. The property sits up high, with the back falling onto a winding river that provides for beautiful views and tranquil sounds. There are also many overhanging cliffs and a dam on the property.

There are many positive aspects of this place, one being that there are enough houses within walking distance to preserve the ancient tradition of monks walking on alms round each morning to collect their food. This is an essential aspect of a monk’s duties and something that has been difficult to keep up for other monasteries in the west.

We firmly believe that this place will be a place of great benefit to many people. When people come to listen, learn and practice the Dhamma – teachings on good moral conduct, making the mind peaceful, and developing true wisdom within our minds – this will surely be of benefit to people’s lives, their happiness, and people around them.

A FOREST MONASTERY PROVIDES SECLUSION FOR MEDITATION, YET IS STILL ACCESSIBLE TO THE PEOPLE.

One hour Southwest of Sydney city or 20 minutes from Wollongong City, visitors entering the monastery are greeted with a feeling of peace and tranquility. The natural surroundings of forest, water, cliffs, and the sight of the monks of the Ajahn Chah lineage, provides a feeling that this is a true forest monastery where the emphasis is on the practice of the Buddha’s teachings in suitable environment.

The monastery provides a unique opportunity for the practicing monastic community. The relatively flat land and large forest provide seclusion for meditation practice. The back of the monastery, drops down 80 metres in to the Cataract River, a 23km water source for the Sydney people.

There are many caves and overhanging cliffs ideal for seclusion and meditation retreats.The small dwellings are simple and austere. They have no electricity, heating, or toilets. They are simple enough for a forest monk to practice meditation and take rest.

Monks staying here will go on alms at 7:30am to the nearby houses around Wollondilly Ave, Wilton (off Douglas Park Drive) on most days of the week. This is a tradition that has been followed since the time of the Buddha and that is still kept within the Thai forest tradition. This is generally considered to be a way to support the local monks who by the rules set down by the Buddha are not allowed to cook their own food, store food, nor eat past midday, and thus must rely on the laypeople to offer food to them for their daily meal. In this way, the monks and the laypeople have an interdependent relationship, where monks rely on the laypeople, and the act of giving done by the laypeople is considered meritorious and essential for the development of higher states of mind.

If you would like to offer alms food, then food, fruit or packaged foods that do not need to be cooked are preferred. Also, on alms round money is not accepted. Generally, in Thailand, the laypeople will greet the monks by putting their palms together facing upwards in front of their chest.

On 12 October 2013, we were very fortunate to receive and enshrine a sacred Buddha statue from His Holiness, the Somdet Sangharaja Phra Nyanasamvara, for the occasion of his 100th birthday. Sadly, less than 2 weeks later, His Holiness passed away. Throughout his life His Holiness did his utmost to spread Buddhism to the West and we hope that we can carry on this wish, by building Bodhisaddha Forest Monastery into one that spreads the teachings of the Buddha, on peace and happiness, to the people.

The Muchalinda Dam was built to house the sacred Buddha. It is a large 220m diameter octagon dam with 8 circles, symbolising the Noble Eightfold Path. After 18 months of construction, the Muchalinda Dam with the Buddha House in the middle was completed. The consecration ceremony was held on the September 2015 and was well-attended with many distinguished guests.

Pictured from left to right: Mr.Vasin Ruangprateepsaeng, Minister of the Royal Thai Embassy; Mr John Yee, Director, Hong Australia Corp.; HE Mr. Teerathep Bromvongsanon, Consul General of Thailand; Nina Yee, President, Bodhikusuma Buddhist & Meditation Centre; HE Mr. Chirachai Punkrasin, Ambassador of Thailand; Mr. Suwit Khunkitti, Former Deputy Prime Minister of Thailand; HE Dr. Yayan Mulyana, Consul General of Indonesia.

Today, visitors use the Muchalinda Dam as a place of worship and practice. Many will walk meditation around, while some even stay up all night to walk 108 times around.

Luang Por Liem Thithadhammo, abbot of Wat Nong Pah Pong, head of the Ajahn Chah Lineage, came for his second visit to Bodhisaddha, in February 2016. We were very fortunate to have Luang Por Liem and his monks for the Magha Puja Ceremony (picture above) and for the installation of the stone carved monastery sign.

Luang Por Liem Thithadhammo, abbot of Wat Nong Pah Pong, head of the Ajahn Chah Lineage, came for his second visit to Bodhisaddha, in February 2016. We were very fortunate to have Luang Por Liem and his monks for the Magha Puja Ceremony (picture above) and for the installation of the stone carved monastery sign.

Luang Por Sumedho, most senior Western disciple of the Venerable Ajahn Chah, visited us in April 2016 for the 4th anniversary celebrations of the monastery. We were very fortunate to have Luang Por visit us for the first time.

Luang Por Sumedho, most senior Western disciple of the Venerable Ajahn Chah, visited us in April 2016 for the 4th anniversary celebrations of the monastery. We were very fortunate to have Luang Por visit us for the first time.

Kathina is the ceremony that only takes place in the one month period (late October, or early November) after at least five monks have completed the three month vassa (rains-retreat). This once-a-year ceremony is considered the largest alms-giving opportunity of the Buddhist year. The laity come together to express their appreciation to the Sangha community with offerings of robes and requisites. After the vassa, monks may again venture beyond the monastery, to continue the life of a mendicant wanderer.

In November 2016, Bodhisaddha held its first Kathina ceremony with 5 monks spending the rains retreat and 10 monks in attendance for the ceremony. It was a very harmonious and uplifting occasion.